People often ask me how they can live, work, hike, camp, sea kayak, raft, and [insert verb here] more safely in areas that grizzly bears and black bears live. Keen to help, I’ve done lots of internet searches over the years to see if I can find a go-to-website that provides easy access to the collection of resources that I often use in my work. I haven’t quite found what I’m looking for but think I’ve found a way to help. I can point the way to some of the best advice, standards, and practices that we have available relevant to safety bear country so that more people can find them: one of the many reasons I started this blog.

This post provides some direction to help people live, work, and recreate more peacefully in bear country. So let’s start with the bear basics.

I know it’s easy to find heaps of information aimed at staying safe around bears. For many people, what’s not so easy to find is reliable information: the kind that is based on the knowledge and experience of leading bear experts. I’m grateful for the high quality resources that are available because it makes my job so much easier. Now, I’d like to help make it easier for others to find them so that they can avoid getting lost in a maze of misinformation. In this post, you’ll read about how you can learn the basics of safety in bear country. In subsequent posts, I’ll delve into resources that are available to help you to prevent and deter bears from gaining access to human food and other attractants, and then I’ll get into situation specific topics that I commonly get asked about.

First Things First: Where Are You Now?

I’m comfortable working and recreating in bear country. This is because I have knowledge and understanding about bears and various factors—related to the environment, bears and people—influencing my level of risk when I’m around them. I can identify hazards associated with human–bear interactions and much more often than not there are actions that I can take to reduce my level of risk—for me, for other people that are in the area after me, and for bears. My real risk and my perceived risk are probably around the same level. But people’s understanding of bears and human–bear interactions vary considerably for a diversity of reasons including what they’ve learned from others and their previous experiences with bears. When people and bears interact, some people’s real risk does not match their perceived risk (it is much greater for some, much less for others). I’ll give you some examples.

At one end of the spectrum, some people find bears so scary that the very thought of encountering the beasts keeps them up at night. I’ve set out on lots of wilderness trips with one or more people in the group very worried about bears. It was a joy for me to watch them relax as the kilometers and days rolled by, they experienced the wonders of wilderness, and they learned more about bears and preventing problems with them. Cumulative mornings met safe and sound probably help too.

At the other end of the spectrum, I’ve been astonished by people unaware of the risk that bears pose, sometimes despite warnings! Numerous times, I’ve seen people crowding bears to take pictures of them, pushing the bear to the point that it’s clear to me, by its body language, that it feels stressed. I’ve seen similar situations on YouTube videos and in nature and adventure films. In many of these interactions, I see little or no indication that the people involved understand the messages that the bear is giving them. Often the bear is saying “you are getting too close for comfort.”

While people can and do interact in close proximity with bears relatively safely in some places and in some situations, such as at McNeil River State Game Sanctuary and Refuge and Brooks River in Katmai National Park and Preserve, these areas are not typical of what one can expect to find when travelling through most of the range of bears in North America. These and some other areas are well-managed specifically for bear viewing with the dual goals of keeping people safe and conserving bears. Regardless of where you are, managed area or not, it is never safe to approach bears; that is, unless it’s a bear behind bars in a zoo (as some of my students like to point out on their test.)

I also know lots of people who stand somewhere between these viewpoints. Most of these people have experience interacting with bears. Many of them appreciate and respect bears, knowing that bears can be dangerous but that risk of being seriously harmed by them is relatively low. Even so, I often encounter people who could be doing more to make situations safer for themselves and others, and to prevent bears from getting into trouble with people.

The Safety in Bear Country Society puts the treats that bears and people pose to each other into perspective.

“Bears are powerful carnivores, well-equipped to do each other serious harm. Yet they have also evolved ways to minimize the chance of injuring each other. Most encounters between bears are characterized by tolerance and restraint. It’s the same when they meet up with people: they usually try to avoid a confrontation. Countless interactions between people and bears occur without any harm. A meeting … a mutual departure … no attack … no injury … no news. Despite their formidable strength and their potential for aggressive, violent encounters between bears and humans are surprisingly rare. In North America, on average three people die from bear attacks each year, although injuries occur more frequently. On some occasions, it may be necessary to destroy a bear to defend a person’s life or property. Regrettably, hundreds of other bears are also shot and killed every year – needlessly.” — Staying Safe in Bear Country DVD, Safety in Bear Country Society 2007

Reducing Your Risk in Bear Country

To live, work, and recreate more safely in bear country, set your sights on increasing knowledge and understanding about bears and their behaviour; bears don’t need to be scary; they’re definitely not harmless. Grizzly bears are much more dangerous than black bears but the overall risk of being seriously injured or killed by a bear is relatively low. There’s a lot that you can do to manage your risk to make it even lower and it’s relatively easy to learn how.

John Hechtel, Safety in Bear Country Society, has wisdom to offer about the best way to your risk around bears:

“The best way to minimize conflicts with bears is by practicing prevention. Though bears are forgiving of almost all human behavior by following some simple rules you can reduce your chances of encountering a bear, and just as important, of attracting one. But despite the best precautions, you still may occasionally meet a bear. Bears often display many of the same types of behaviors toward humans that they use with each other, therefore, the safest way to reduce risk during an encounter is to have knowledge and understanding of their behavior and motivation. You should be able to anticipate the most common situations where you might encounter bears and it’s a good idea to mentally practice how you should respond. This knowledge and preparation can empower you to act appropriately around bears and avoid an attack. You have control over most of the important factors that determine your safety. Safety is no accident. It’s your responsibility.” — Staying Safe in Bear Country DVD, Safety in Bear Country Society 2007

Safety in Bear Country: The Basics

You can take responsibility for your safety in bear country by taking a course from a well-qualified instructor, and by travelling with and learning from others who have knowledge about bears and experience with them. Many government and non-government organizations provide high quality bear safety information and interpretive programs. However, there is also a lot of low quality information (misinformation, missing important information) out there, in brochures, on signs, on the internet. I tell my students that if they find information that conflicts with the Safety in Bear Country Society, it’s not reliable. Once you have the basics, there’s also a lot that you can do to learn or continue to learn about bears on your own.

Here are some of the basics to get you going on the path to staying safe in bear country:

- Take a course for bear awareness and safety from someone that is well-qualified to teach it.

- Watch the video Staying Safe in Bear Country: A Behavioral-Based Approach to Reducing Risk by the Safety in Bear Country Society. The script for the video is available here. Yukon Environment has produced a brochure How You Can Stay Safe in Bear Country based on the video. Review this information, as many times as needed, so that you know the material well.

- As appropriate given your situation, watch other modules of Safety in Bear Country Society video series: Staying Safe in Bear Country: A Behavioral-Based Approach to Reducing Risk

- Mentally rehearse how you will respond if you do encounter a bear. The Safety in Bear Country Society tells you to do this. I do this. I know other bear experts who do this.

- Get training and carry bear deterrent spray and know its limitations and when and how to use it. Refer back to the Staying Safe in Bear Country video and How You can Stay Safe in Bear Country brochure for important information about the use of bear deterrent spray. Learn when and how to use bear deterrent spray, the limitations of it’s use, and regulatory restrictions and requirements governing its use (Refer to first point in this list.)

- Expand your knowledge by reading Bear Attacks: their causes and avoidance. Stephen Herrero is world-renowned bear specialist and the leading expert on bear attacks in North America. Don’t just read the sections about bear attacks. I know a few people who did that and they scared the heck out of themselves. You need to read the entire book to learn about bears and their behaviour so that you have the appropriate context for considering the worst that could happen and so that you can improve the probability of better outcomes, if and as needed.

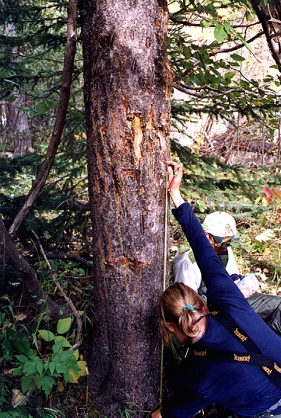

- Keep learning. Expand your naturalist skills so that you can identify food plants and habitats used by bears. If you can identify plants that bears eat and interpret sign associated with bear activity (another post to add to my list), you’ll be well on your way to being able to assess your probability of encountering a bear and be better able to adjust your behaviour accordingly.

Important Note Regarding Bear Spray: Ensure that bear spray is designed for the purposes of deterring bears and approved by the appropriate regulatory agencies (for example, Health Canada in Canada and Environmental Protection Agency in the U.S.A.) Get up-to-date information regarding regulatory restrictions and requirements (national, provincial, state, local levels of government) for bear spray including it’s purchase, use, transportation, and disposal. For example, there are requirements for the disposal of bear spray where I live and there are also restrictions or requirements that apply to the transportation of bear spray across borders and in aircraft that I need to inform myself about when I travel. These vary among government jurisdictions and I have seen some changes over time. Read the label on the canister of bear deterrent spray and use it according to instructions. Proper training will cover these important points and more.

Do you need practice identifying bear species, black bear or grizzly bear?

The Be Bear Aware Campaign has a bear species identification card (presented below) that many organizations use to teach species identification. This site also has a bear identification test.

You can also find the Be Bear AwareTM bear species identification card and an accompanying video on the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife website.

Students often ask me to tell them about my scariest bear story.

I don’t have any bear stories with serious outcomes for me or the people I was with. Over the course of my career, I can think of five times where the probability of the situation going sideways was clearly elevated. They all worked out with no harm done, to me or the bear. In all but one of these situations, I could see there was a lot that I could have done to not get myself in that situation in the first place. Here’s one of those stories:

I warn my students, if today is the only time that you think about how to respond in a bear encounter, then it’s unlikely that you’ll remember any of what’s needed if you’re suddenly confronted by a bear. Case in point: in one of the few sudden close encounters that I’ve had with a grizzly bear, first and foremost, I needed to connect with my hiking partner who was intent on scrambling past me in a panic to get away. I did a poor job of teaching her how to respond in such a situation. In the time, before I started working with bears, I had encounters with where I responded in a way that I would not even consider now.

To back up a bit: It’s not good to surprise bears, particularly grizzly bears because they’re more likely to respond defensively if they feel threatened. Black bears usually, but not always, flee when they feel threatened. If I think there’s potential for encountering a bear, I avoid sudden encounters with them by calling out “yo bear”as I travel, varying the sound level and timing of my calls based on my ongoing assessment of risk. If the probability of encountering bears seems high—for example, when I’m walking along a noisy creek, it’s pouring rain, the wind is blowing in my face, and there are lots of bear foods around—I call louder and more frequently and sometimes I even slow down my rate of travel.

This day was different. It was one of the few times that I’ve decided to hike silently when everything around me screamed at me to do otherwise. I was at the junction of two major wildlife trails running through high quality bear habitat. I was seeing lots of fresh grizzly bear sign including scats (science for poops) and tracks of adults and cubs so the probability of a bear being nearby was high. The visibility was poor because trees and shrubs were blocking my view so it was unlikely that I’d see any bears until it was too late. Plus wind was gently blowing in my face so it was unlikely a bear would be able to detect me in advance and make a move to avoid me, which most bears will do if you give them the chance. I remember thinking, if I ignore my better judgement what are the odds of surprising a grizzly bear, in this place, at this moment—after all these years of practicing prevention. I pushed on, hoping for the best.

Some might ask why I ignored my training and gut feelings (or some might even wonder why I would put so much thought into it in the first place). There was a commercial rafting group ahead. The owner of the company had previously asked us to keep a low profile on the river if we saw them. He wanted his guests to have a pristine wilderness experience, ideally without seeing another soul on the river, not even researchers. Me: I had lots of work to get done. I was trying to keep everybody happy.

Well, we jumped right into it. Suddenly, there we were, the bear included, less than a few metres apart from each other, all of us awash in stress hormones. “Stop. Get beside me”, I breathed, and then in synchrony, my partner and I faced the bear; I pulled my bear spray; the bear reeled away. Flooded with relief, we watched the butt end of a young grizzly bear that was running just as fast as it could, heading to the river. We were safe. The rafters got an incredible observation of a bear (with no idea of why it was running) and we didn’t wreck their wilderness experience. Even so, I was mad at myself because it happened. We were lucky it was a young bear on its own. Had it been the mother with cubs, whose fresh tracks I was seeing, the probability of being harmed would have been much higher.

On reflecting, I was grateful for the lesson learned. I realized that it was the mental preparation I had done ahead of time that enabled me to respond appropriately without having to think about it, more affirmation that I could do what I needed to do if put to the test. I’m happy to report that with more than two decades of working and recreating in the grizzly bear and black bear country, I’ve never been involved in a serious incident with a bear. Nevertheless, I continue to periodically mentally rehearse my response to encounters, and sometimes I need to apply my knowledge. You should practice too.

I tell my students that they need to pass a quiz to get their certificate for the course but I also tell them, “the quiz is pretty straight forward; I’m not trying to trick you. But if ever there’s a test, it will be a bear that’s delivering it.” Most and hopefully all of my students will never be severely tested by a bear, but if I teach enough of them odds are one or a few will be. If put to the test, I want them to pass.

Conversely, I do have lots of stories about bears that I knew well that were known to have been or probably were killed or seriously injured by people.

There ought to be a people awareness and safety course for bears. But short of this, a major part of my bear awareness and safety course is to help my students to prevent human-caused bear moralities associated with undesirable human–bear interactions: a win–win approach for people and bears.

Learn more about bears and share your knowledge with others.

In the short days of winter when bears are not active, take time to learn more about bears and to share your knowledge with others.

Some More Interesting Stuff

- You can find a complete list of references that I refer to in this post and some more of my favorite resources at my Bear Awareness and Safety page.

- If you want more practice identifying bears species, the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee has posted links to several websites that have online tests for bear species identification.

- Outside Online has a good article Shoot or Spray? The Best Way to Stop a Charging Bear based on research regarding a Efficacy of Bear Deterrent Spray in Alaska (published 2008) and Efficacy of Firearms for Bear Deterrence in Alaska (published 2012).

Caro

Fantastic compilation of resources interwoven with your personal experiences and raft of professional knowledge. Everyone should bookmark this page and keep coming back to it to read through all the links. The more we learn and refresh our memories, the safer we’ll all be – bears and humans. Thanks for this Deb – looking forward to more!

Deb Wellwood

Wow. Thank you kindly for your feedback. This should keep me going for a while. It’s good to know the mix works for you. I have many more posts waiting to leap off my to-do-list. Please jump in with any requests, comments or questions. Best wishes!

Megan Dafoe

So great to read this and see how you are doing. Great information by the way. Hope the ankle has healed nicely.

Deb Wellwood

Thanks Megan! I’m running again and it feels like new. I wish I could say the same about my cardio…one-step-at-a-time…